You have a new version of an old product, and it’s great: better functionality for most users and lower production costs than previous models. You’ve hit a technological home run. But how do you price it?

This is a nice problem to have, but it’s definitely a problem. Set your price low and you earn moderate profit margins on large volume—if the low price doesn’t spook buyers into thinking it’s a low-quality product. Price high and you earn high profit margins on low volume, as most users are slow to adopt new technology.

Price discrimination is one option. We economists use the term when a product is sold at different prices to different buyers. (It does not imply any racial or religious bias.) A classic example was airline tickets, which used to be cheaper for trips that extended over a weekend. Airlines figured that business customers were not very price sensitive, but recreational travelers were. The airlines couldn’t very well set the price based on what the customer said the purpose of the trip was, so they used the Saturday night stay. People staying over on a Saturday night were probably recreational, whereas the Monday departure and Friday return was most likely business.

The company with new technology might quote a high price to some customers, but offer discounts to those who are most sensitive to price. To structure the best possible deal, though, you need a full understanding of the transaction.

A sale is not just a transfer of a product for money. Take my consulting services. It looks like I swap my expertise for cash. That’s accurate, but not complete. Some customers are prestigious and influential. I garner not just cash but also a halo effect when I talk about my client list, as well as referrals to new customers. My client may gain the confidence of the board of directors, who appreciate management that uses the best expertise available. So the transaction is a bundle of features being swapped.

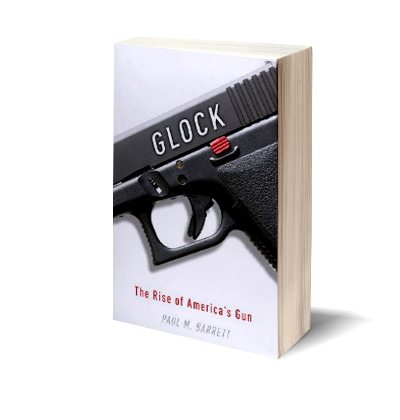

The new book about a revolutionary gun (Paul M. Barrett, Glock: The Rise of America’s Gun) provides a great example. Glock kept its price high to the public, but offered deals to police departments across the United States. The company offered to swap new Glock pistols for old police revolvers, effectively discounting their product. The police departments liked getting new, more effective guns with little cash outlay. The Glock company sold the used revolvers to recover their manufacturing costs on the new guns. The police departments threw something else into the bargain: credibility. The police won’t use an unreliable, inaccurate gun, right? So the Glock must be a good product. After seeing their local police officers, as well as TV stars, packing the new black plastic pistols, everyday people went to their local gun stores and paid the high price. The company’s profit margin on the retail sales was huge.

Your product breakthrough will have to be priced based on its own market dynamics, but here is the basic lesson: look for a way to quietly discount to influential users, while pricing high to others.